Your old refrigerator may contribute as much as 15% to your electricity bill (Marsh, 2024). Refrigerators need electricity 24/7, with older models consuming up to 1,700 kilowatthours (kWh) per year. Replacing it with an energy efficient model may seem like a good way to save money and reduce your environmental impact, but is it really? And what exactly happens to a fridge when it’s picked up for disposal? Let’s find out.

When should you replace your refrigerator? It depends!

Generally, if it’s still working, it’s a good idea to keep using an appliance. In the case of refrigerators, however, durability doesn’t always equal economic or environmental sustainability. Hence, the best time to replace a working refrigerator depends on its age, your local electricity mix, and financial incentives.

The factors that impact your refrigerator’s “best by” date:

- Age: The older your fridge, the less energy efficient it was to begin with. Over time, your fridge becomes less efficient because its foam insulation degrades with age, meaning your fridge’s compressor uses more and more electricity to maintain the same target temperature (Cappelletti et al., 2022). Once your fridge shows signs of breaking down (Friday, 2022), like excessive condensation, ice buildup, or unusual sounds, it may be time to replace it. The typical lifespan for a fridge is around 15 years, although lifespans over 20 years aren’t uncommon, either.

- Electricity mix: A carbon-intensive electricity source makes running an older fridge that uses increasing amounts of energy less sustainable (Lewandowska et al., 2021). Electricity made by burning fossil fuels like coal, peat, oil, or gas (natural or not) is more carbon-intensive than electricity sourced from wind, solar, hydro, or nuclear energy. If your electricity mix is clean, using a fridge beyond its average lifespan, for as long as it’s in good working order, may be a more sustainable choice.

- Electricity cost and other financial incentives: The cheaper your electricity, the longer it will take to make the money spent on a new fridge back through cost savings. But if you have access to a rebate program that only covers working appliances, such as Mass Save in Massachusetts, you might want to dispose of an aging fridge before it breaks, or you’ll be responsible for disposal costs. In some areas, however, appliance disposal may be covered by manufacturers, e.g., in British Columbia and Québec, Canada. Some appliance retailers will also take your old fridge for free when you purchase a new one from them. In those cases, it doesn’t matter whether or not your fridge still works.

Typically, a new fridge of the same size as your old one will use much less electricity and could save you 5-10% on your electricity bill. You might, however, only save a few percent, and, unless your electricity is fossil fuel-based, replacing your fridge likely won’t help the environment. What’s more, if you upgrade to a larger fridge with more modern features, any potential savings or positive environmental impact might get wiped out entirely.

You can use the matrix below to guide your decision.

| Age & Condition | Energy Mix | Electricity Cost | Incentives | Recommendation |

| <15 yrs, good | Any mix | Any | Any | Keep using |

| 12 to 15 yrs, good | Clean | Low–Medium | None | Keep using |

| 12 to 15 yrs, good | Carbon-Intensive | Medium–High | None | Consider Replacing |

| 12 to 15 yrs, good | Any mix | Any cost | Rebate only valid for working fridge | Replace before failure or when signs of ageing accumulate |

| >15 yrs, good | Clean | Low | None | Keep using |

| >15 yrs, good | Clean | Medium–High | Any | Consider replacing |

| >15 yrs, good | Carbon-Intensive | Any | Any | Replace soon |

If you do decide to get rid of your old refrigerator junk, removal services are a super convenient option. 1-800-GOT-JUNK? makes the process incredibly easy—they handle everything for you, including recycling and donation of items where possible.

How to tell the age of your refrigerator

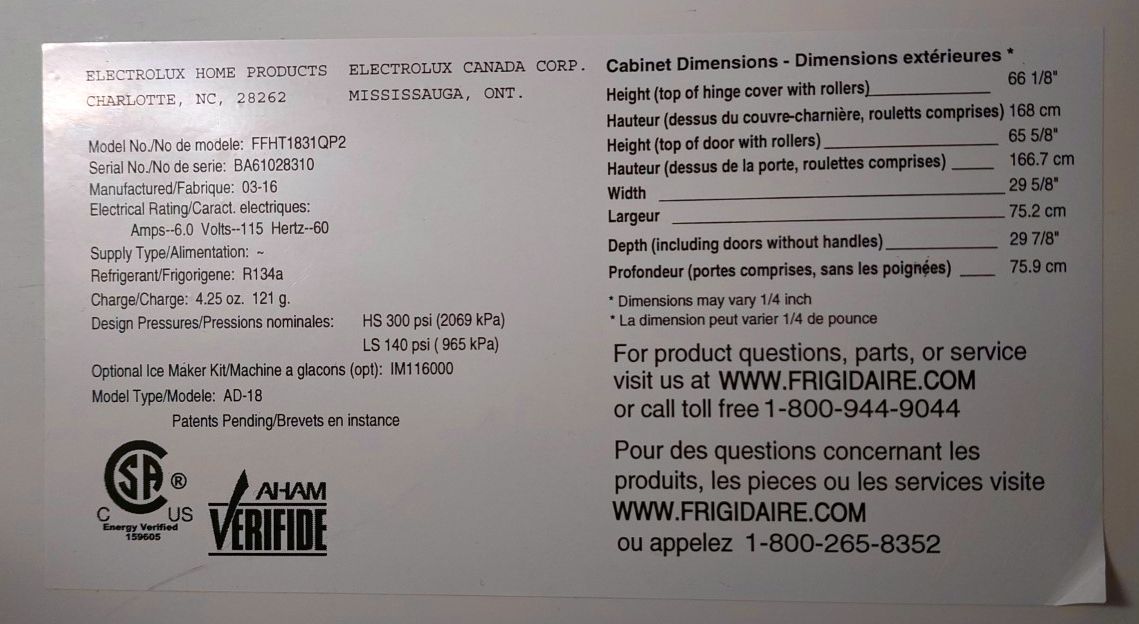

You can find your refrigerator’s manufacturing date on the label that also contains its model and serial numbers. That label is typically placed inside the fridge or on its back. You can also look up the compressor’s label at the back of the unit. If the label doesn’t list a manufacturing date, you can use the Appliance Age Finder to decode the serial and model numbers of your fridge.

Per its label, our fridge was manufactured in March of 2016.

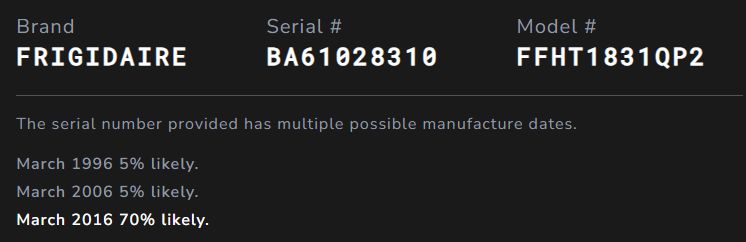

The Appliance Age Finder correctly dated our model with a 70% likelihood.

How does 1-800-GOT-JUNK? handle refrigerator disposals?

Between January and October of 2025, 1-800-GOT-JUNK? has picked up around 8,500 refrigerators across all its locations in the U.S., Canada, and Australia. With approximately 200 locations worldwide, every 1-800-GOT-JUNK? location handles about one fridge per week on average, but typically more during the summer months and less during the rest of the year. Overall, fridges make up about 1% of the company’s total volume, making it one of the most commonly disposed of appliances. In other words, each location is well-versed in handling refrigerator disposals.

What happens when 1-800-GOT-JUNK? picks up a fridge?

As with every item the company whisks away, Truck Team Members will safely remove your fridge from wherever it’s located inside or outside your house, take care of cleanup, and handle the item’s disposal. All you have to do is point, or do you?

Almost. Matthew Corey, Director of Field Operations at 1-800-GOT-JUNK? notes:

"Some units may have a connected water line, which must be disconnected by the homeowner, as Truck Team Members do not handle plumbing, electrical, etc."

So while you won’t have to move your fridge to the curbside for pickup, nor take it down the staircase, you do have to unplug it yourself.

What happens with a refrigerator after it’s been picked up?

The majority of fridges 1-800-GOT-JUNK? picks up are taken to a recycling facility or a metal recovery yard. Approximately 2 in 100 fridges (2% of total pickups) are donated. Matthew Corey explains that this happens on a case-by-case basis, and David Gilmour, Director of Product Marketing at 1-800-GOT-JUNK?, notes it’s an informal process, which depends on the location’s relationship with local donation partners.

Before Truck Team Members drop off a refrigerator for recycling or donation, they log what they picked up. This allows them to track the volume of those items, as well as the materials they are made up of.

Taylor Sharpe, Senior Product Manager at 1-800-GOT-JUNK?, on how the material logging works:

"The truck team would estimate the total volume of each material that makes up the fridge. Ex. if a fridge is generally 50% metal and 50% plastic and as a whole it takes up 1/8 of a truck, they would create 2 separate submissions; one for metal - 1/16 of the truck, and 1 for plastic - 1/16 of the truck. In the background, the system calculates the weight based on the volume:weight data we have from the EPA [U.S. Environmental Protection Agency]."

Within its internal database, 1-800-GOT-JUNK? also tracks the repurpose rate by material type. Refrigerators are generally made up of metal, plastic, glass, and insulating foam. 1-800-GOT-JUNK? doesn’t track foam. What the database tells us about the remaining materials found in a fridge is that around 80% of metal, 40% of plastic, and 39% of glass is repurposed. However, since the database doesn’t distinguish between individual items, this isn’t necessarily true for refrigerators. So let’s explore what happens to refrigerators at a recycling facility in North America.

What happens to fridges at a recycling or disposal facility?

The refrigerants contained in refrigerators are considered hazardous waste. That’s why federal regulations in the US (Environmental Protection Agency, 2015) and Canada (Canada & C., 2024) require that certified technicians recover refrigerants from the compressor before the rest of the fridge is recycled or disposed of. Facilities that accept refrigerators for disposal have to follow these local regulations to prevent ozone-depleting refrigerants, some of which have high global warming potential (GWP), from escaping into the environment.

Recycling facilities also aim to recover valuable materials like metals, plastics, foam insulation, and glass. According to Mass Save, an appliance recycling program in Massachusetts, “95% of a refrigerator or freezer can be recycled.” (The RCS Network, n.d.). Even some refrigerants can be reclaimed (A-Gas, n.d.) and reused in new refrigerators.

The exact recycling process depends on local conditions. Areas with high refrigerator recycling volumes, high demand for recycled materials, and strict environmental standards tend to have entire factories dedicated to processing fridges (Cebi, 2025), which allows them to recover almost all recyclables. In North America, the conditions for recycling large appliances are less ideal.

What’s the problem with refrigerator recycling in North America?

In most of North America, recyclers remove refrigerants and metals like steel, copper, and aluminum. The rest of the fridge, however, including remaining recyclable materials, is landfilled.

We spoke with Chris Campbell, Director of Field Operations at MARR (Major Appliance Recycling Roundtable), a non-profit stewardship agency that runs the stewardship plan for end-of-life major household appliances under the Recycling Regulation in British Columbia (BC), Canada.

Chris told us:

"In every jurisdiction in North America, except for Québec, Canada, appliances are processed through the automotive recycling process because automobile shredders are the only facilities that can take on appliances."

Automobile shredding is an old process, designed to extract metals, i.e., the most lucrative materials. From Chris we learned that all the plastic, insulating foam, glass, and everything else left over after the metal extraction “is wrapped up in automotive residue and sent to landfill.” While trashing recyclable materials isn’t ideal, possibly the bigger problem with refrigerators going through this process is the leakage of ozone-depleting substances (ODSs) into the atmosphere.

You see, refrigerants–or chemicals closely related to them–aren’t just good for cooling. The foam insulation found in the cabinet and door walls of refrigerators contains refrigerant-like chemicals. These so-called blowing agents make spray foam insulation expand to fill any given space. In refrigerators manufactured prior to 2005, the spray foam contains blowing agents with a high GWP and ozone-depleting potential (ODP) (Todtenhagen, 2021).

Throughout a refrigerator’s lifespan, these chemicals remain stuck in the foam, though they may slowly evaporate as the foam breaks down. When the appliance is shredded, any remaining refrigerant gases contained in the foam, often more than half the original amount, are released (Dehoust & Schüler, 2010). In Europe, fully encapsulated refrigerator recycling plants capture gases released during shredding. Chris says that up to a third of the refrigerants collected at these plants comes from the foam insulation. Unlike the refrigerant contained in the compressor, most North American recycling facilities can’t recover refrigerants from spray foam.

When the last ozone-depleting chemicals were banned in 2005, manufacturers moved to blowing agents that didn’t have an ODP, but even today they still have some GWP. MARR found that 12-15% of appliances collected in BC still contain refrigerants with a high ODP, including R-12 or R-22, which haven’t been produced since 1994 and 2010, respectively.

Should you hold onto your fridge until full recycling is available?

Recyclers and stewardship programs across North America are investigating the options for processing and recycling residual materials. MARR, for example, is planning for a fridge recycling plant, but has yet to receive sufficient political support. Unfortunately, it will take some time until refrigerators will be fully recyclable in North America.

So if you’re ready to dispose of your ageing refrigerator, know this: The end-of-life pollution caused by recycling a refrigerator in North America might be negligible compared to the damage done by a carbon-intensive electricity mix.